An excerpt from

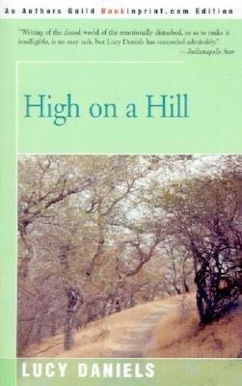

High on a Hill

The residents of the town of Perthville knew Holly Springs Hospital for Nervous and Mental Disorders simply as “The Hill.” And they used that name often in a variety of jokes and threats.

“One more day like this,” cab-driver Herb Shumann would groan, “just one more, and they’ll have me on The Hill.”

George Purdy, who ran Purdy’s Select Grocery, would smile in response as he pushed Herb’s pack of cigarettes across the counter to him. “I’ll meet you there,” he’d say. “That’s where I’m going when I get rich.”

Holly Springs was a private hospital rated among the top ten in the United States. It accommodated some five hundred patients—men and women—and required, all told, an almost equal number of employees. It boasted a nine-hole golf course and encompassed an area as large as Perthville itself. And because of the high cost of prolonged psychiatric treatment, many of the patients came from well-to-do families.

There was a constant parade of new patients at Holly Springs. Most of them gradually found at least a semblance of serenity and went home. For others, that search required years. And still others, too old and tired to try, never found peace at all, but settled down without it to live out their lives at Holly Springs.

Carson Gaitors had a joke about this. After three years in the hospital, she was at last on a privileged hall and making plans to work in the city; so the newer patients regarded her as an authority. “There’s only two types ever leave here,” she’d say, her heavy breasts shaking with amusement, “only two−alcoholics and the help.”

When she told that to Dr. Holliday, the corpulent director of the hospital laughed, too. “Now, Mrs. Gaitors,” he boomed in his friendly drawl. “I don’t think that’s fair. I fit in both categories, and here I am. Still here.”

But for other people, it was not a joking matter. Pretty eighteen-year-old Evelyn Barrow, after six months on Hall 3, still insisted she’d been shanghaied. “It’s my mother should be here,” she said again and again. “She’s the one; they let her trick them.”

Jack Isaacs’ dark eyes looked dead and far away when people talked about leaving the hospital. Sometimes his lips would tremble, and if he did not walk away quickly, his voice might cry out, “Lucie, Lucie!”

Nineteen-year-old Ben Womble did not allow himself to think about leaving Holly Springs. When other people spoke of it, he simply did not hear; and when, uninstigated, the frightening idea crept into his mind, the panic it aroused acted as an automatic switch-on device for the comforting void he had painstakingly developed.

For the world-celebrated surgeon, Jonathan Stoughton, Holly Springs was a tomb. When it rained or snowed and the nurses herded them to O.T. and gym through the musty black maze of underground tunnels, he felt as if he had been buried alive. All his life the old doctor had loved to walk in the rain, to smell the fresh earth, and feel the cool dampness on his face. Here in this grave he was not only denied that, but forced to walk past carts of garbage—of orange skins and oatmeal scrapings and rusty lettuce leaves, guarded by moldy little men who stood beside those carts and stared as if watching a circus parade.

But now it was April. Soon the rains would be over and the long, hot days of summer on their way. Though they were scarcely visible under her starched white coat, Martha McLeod, director of the hospital’s women’s division, had taken out her gingham dresses. And she spent all her free time—except that demanded by Tinker, her cat—spading earth for the tomato plants she planned to set out.

It was a busy place, Holly Springs Hospital, like a million other places. Yet it was a world unto itself, a world of no specified dimensions or description, representing something different for each person—a prison, a refuge, a job, a dedication, life, death, the beginning, and the end.